New York City has always had its share of recluses. Many remain anonymous after years of seclusion behind apartment walls, others become infamous later in life or after death.

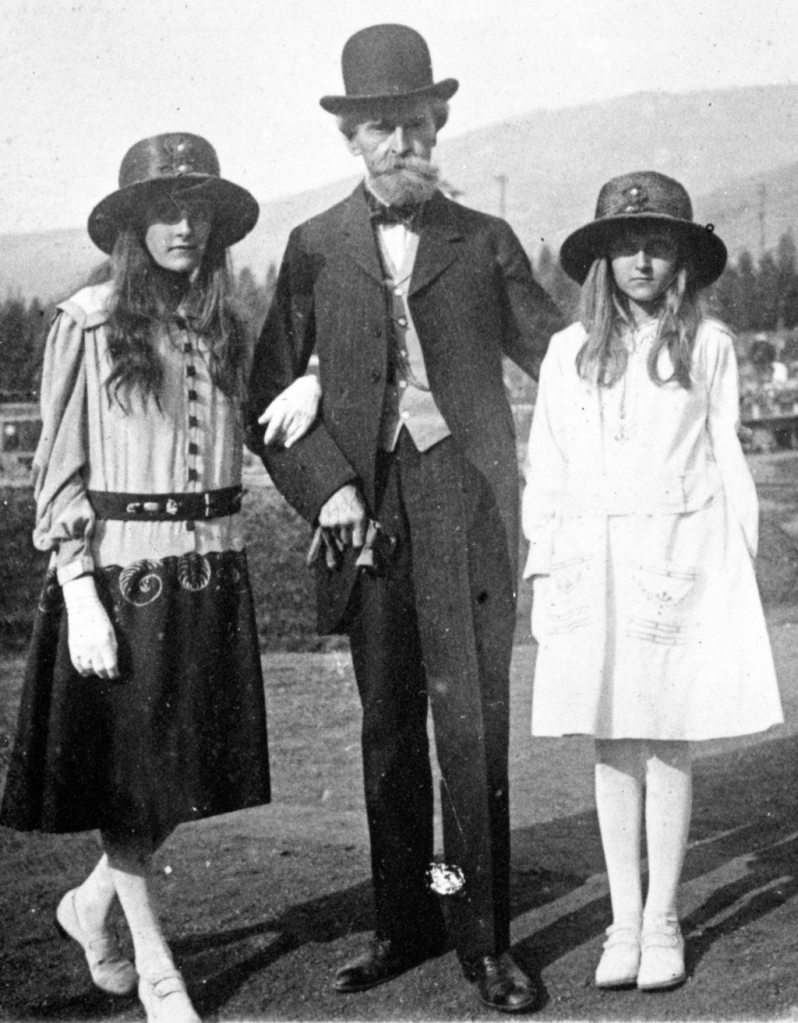

Huguette Clark (above photo) falls into the latter category. More than a decade ago, headlines appeared revealing that this forgotten heiress—born in 1906 to rakish copper magnate and Montana senator William A. Clark (below) and his much younger second wife—had been living out the past 20 years in a Manhattan hospital suite, tended to by private nurses.

Following Huguette’s death at Beth Israel Medical Center in 2011, a few weeks shy of her 105th birthday (and with a $300 million fortune to be divvied up), more details of her unusual life came to light.

As a girl (above right), the “Baby Copper Queen” took the path of other rich Gilded Age daughters. She traveled abroad with her parents, studied the violin, graduated from Miss Spence’s School (now Spence), made her debut in society, and married a Princeton graduate described as a “promising young bond salesman” in 1927.

After a divorce in 1930 (Huguette claimed abandonment, her former husband said the marriage had been unconsummated, according to her New York Times obituary), she returned to the palatial twelfth-floor apartment at 907 Fifth Avenue (below) where she had been living with her mother, Anna, since her father’s passing in 1925 at age 86.

Previously, the family resided in a 121-room mansion fronting Fifth Avenue at 77th Street dubbed “Clark’s Folly” because it was so insanely ornate.

Her retreat over the next decades from society events and social outings went unnoticed by the press. Apparently she was content to lead a small life, collecting dolls, visiting the family’s Santa Barbara estate, and staying out of the public eye—a lifestyle her mother seemed to pursue.

“Mrs. Clark did not care for social distinction, nor the obligations that would entail upon my public life,” William Clark once wrote of his wife, according to Bill Dedman’s 2010 NBC News article and photo gallery exploring the family backstory and re-introducing Huguette to contemporary viewers.

When her mother passed away in 1963, Huguette isolated herself even more. It wasn’t until the early 1990s that a frail Huguette arrived at Doctors Hospital on the Upper East Side for treatment for skin cancer lesions that disfigured her face. Doctors removed them, but she opted to stay in the hospital.

She transferred to Beth Israel when it merged with Doctors Hospital…and never left.

Huguette’s reasons for leading much of her life in seclusion from the outside world remain a mystery. She left no diary or trail of clues. Maybe she was simply an introvert, or very much her publicity-shy mother’s daughter. Perhaps her reclusiveness was driven by grief after losing her mother, her father, and in 1919, her sister Andree (second photo on the left), who died at age 16 of meningitis.

What she did leave behind are her paintings. While her father was an avid art collector whose collection of 800 or so paintings, sculptures, and antiquities are now housed at the Corcoran Gallery, Huguette herself was an artist with a focus on portraits, landscapes, and still lifes.

The image above is a self-portrait of the heiress as a young woman. Holding her palette and standing before a canvas, she seems to see herself a serious artist. There’s a softness to her face and form that reveals a comfort in this space, most likely a studio in her Fifth Avenue apartment.

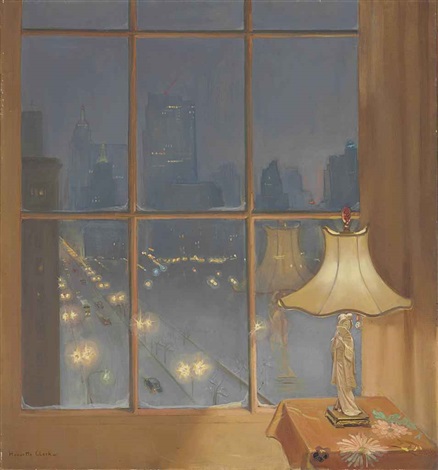

The second and third photos have self-evident titles. The first is “Scene From My Window, Night,” (above) which overlooks Fifth Avenue traffic, illumination from headlights and street lamps, and the modern skyscraper cityscape including the Empire State Building in the background.

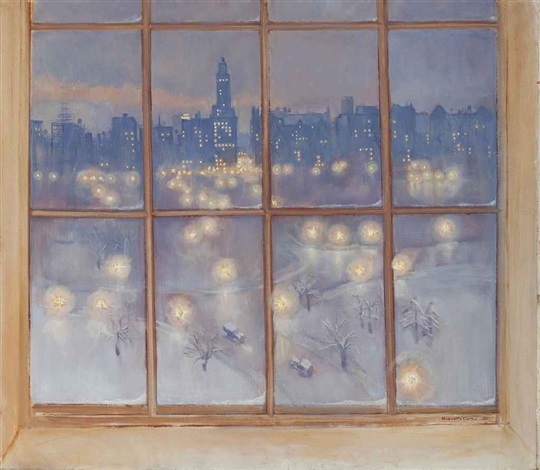

“Scene From My Window—After the Snowstorm” (below) is a similar nocturne featuring soft lights, a snowy Central Park, and prewar apartment buildings like her own in the distance.

When she painted these and others isn’t known. Huguette did exhibit some of her work at the Corcoran Gallery in 1929, and I imagine these date to about that time. If she exhibited elsewhere, I couldn’t find any reference.

The last two paintings intrigue me. On one hand, they’re lovely landscapes showing what makes New York so enchanting: the lights, the snow, the skyline. They seem to have been painted by someone who took pleasure in this side of Manhattan and wanted to recreate it.

On the other hand, the window panes mimic jail bars. Was Huguette’s Fifth Avenue apartment a kind of prison for her? It’s impossible to know, but I prefer to think that this heiress, one of the last human links to the Gilded Age, put herself there by choice—and created a life behind these masonry and glass walls that gave her fulfillment.

[Top image: NBC News; second image: Wikipedia; fourth image: Indianapolis Star; fourth, fifth, and sixth images: Artnet.com]