There’s something about legendary East Village bars that leave New Yorkers mourning them even decades after they close their doors.

The tenth anniversary of the shuttering of Mars Bar in 2011, the gritty dive on Second Avenue and East First Street, merited tribute posts recalling its eclectic mix of regulars. Brownie’s, on Avenue A, pulled the plug in 2002, but Gen X fans are still reminiscing about the bands they saw there.

So it seems unusual that one old-school East Village haunt has no Facebook fan group posting photos and videos, no articles bemoaning the reasons behind its closure.

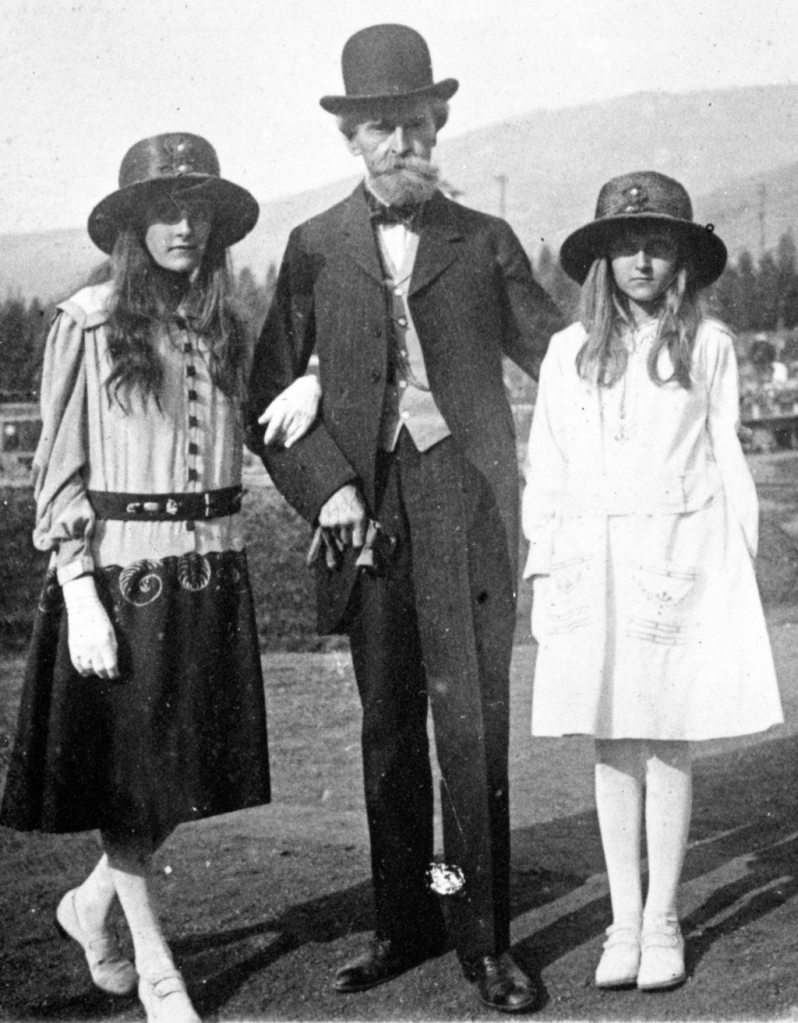

That haunt would be Eileen’s Reno Bar, a hole in the wall at 175 Second Avenue between 11th and 12th Streets. Aside from the circa-1989 photo above, posted in 2015 by Tumblr account noirbynight, and the 1973 photo by Eugene Gordon below with the bar’s neon sign in the background, very little about Eileen’s remains.

The lack of tributes is unusual for a place described by one East Villager who visited in the late 1980s as “a dimly lit, unintentionally surreal bar on the edge of oblivion.” The vibe was “subtle debauchery, in the twilight between the waking life and dreams.”

In other words, Eileen’s was no Irish tavern, or college-crowd sports bar, or glittery nightspot luring stylish young people.

“When you walked in, the first thing you noticed was the leopard skin wallpaper,” said the visitor, who recalls a traditional long bar. Above it, plastic plants hung from the ceiling. “It felt more like a relic of a 1950s lounge, populated by people we think of as living in the shadows in society.”

Writer Gary Indiana included a description of Eileen’s in his 2004 New York article, “One Brief, Scuzzy Moment.” The article focused on the East Village art scene in the mid-1980s, of which Eileen’s played a part.

“A narrow pocket of surrealism on Second Avenue between 11th and 12th, its ceiling surfaced in plastic jade plant—brown plastic jade plant—Eileen’s had its flaccid nights of dead-room tone,” wrote Indiana.

He added that most nights brought in “a steady influx of pre-op transsexuals, clueless walk-ins, bisexual drug dealers, garrulous drunks with a schizophrenic flair . . . and a few black-humored fags like myself, who much preferred the Reno Bar’s nightly Halloween party to clocking the aging process in some drippy gay bar.”

In the article, Indiana recalled one regular, a “laconic and melancholy” man named Joel who drank gin and drove a pickup truck. Later, Indiana learned that Joel was Joel Rifkin—the serial killer from Long Island who preyed on New York City prostitutes.

Who was Eileen? More about her identity isn’t known. Exactly when her Reno Bar opened and closed is also a mystery: I haven’t found a newspaper or website that chronicled its debut or shuttering. (Above photo, about 1940; the space that housed Eileen’s would be the second storefront to the left of the theater, and it doesn’t look like a bar exists there yet.)

In our current era where everything is chronicled via post or image, it’s hard to remember that in the pre-social media world, the closing of a dive bar wouldn’t make the news.

These days, 175 Second Avenue is home to Bar Veloce, a wine bar established in 1999 with several other locations around New York. It fits in to a much different East Village than the one where Eileen’s Reno Bar found its home.

[Top photo: noirbynight; second photo: Eugene Gordon/New-York Historical Society; fouth photo: NYC Department of Records & Information Services]