The Gilded Age ushered in opulent mansions, ostentatious balls, and very conspicuous consumption. But this era synonymous with wealth also brought us the breadline—where impoverished New Yorkers stood in the shadows night after night, waiting their turn to obtain a free meal.

Breadlines (many of which distributed more than bread) proliferated by the turn of the century at Gotham’s missions and benevolent societies created to serve the poor. But the first breadline, where the term originates, started at a fashionable bakery on Broadway and 10th Street in 1876.

Louis Fleischmann, a prosperous Austrian immigrant, owned the Vienna Model Bakery next door to Grace Church on the edge of the Ladies Mile shopping district. One December night, Fleischmann saw a group of men huddled in front of a steam grate beside the store. He brought the men—or “hungry tramps,” as one newspaper described them—some unsold bread left in the bakery. They accepted it eagerly.

More men showed up the next night, forming a quiet line at the back door. Touched by their plight, Fleischmann decided that anyone who queued up by midnight would be given half a loaf of leftover bread, no questions asked. For the next four decades, Fleischmann distributed bread (as well as hot coffee) to sometimes hundreds of men per night on his “breadline,” as it became known.

City newspapers covered Fleischmann’s breadline heavily, some with sympathy and others with a hint of disdain. “Here are men whose lives are not running well—400 small worlds gone to shipwreck,” reported the New York Press in 1902. The New-York Tribune wrote in 1904, “The picturesque and pitiful line of men in the early hours of every morning has become one of the features of the city’s life.”

While New Yorkers debated whether the breadline helped the hungry or instead contributed to “pauperism” and encouraged men to accept handouts, painters, illustrators, and photographers were drawn to Fleischmann’s, where they captured scenes of charity and misery.

Whether painted by social realists such as Everett Shinn and George Luks or shot by news photographers like George Bain, these images depict anonymous men in black hats and coats awaiting their half a loaf and cup of coffee. The humanity of the often faceless men is the focus; the argument as to whether such handouts were helpful or hurtful doesn’t factor in.

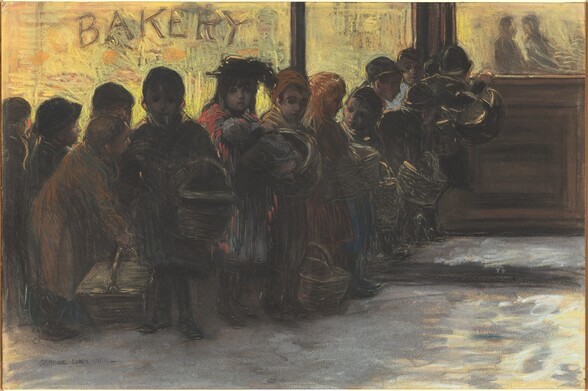

The one curious breadline painting comes from George Luks. Like Everett Shinn, Luks was a member of the Ashcan School, and his work typically reflected a gritty early 20th century city.

In 1900, Luks painted children on a bakery breadline, even though there’s no documentation that young people ever came to Fleischmann’s or any other nighttime breadline. The kids in Luks’ painting have baskets to fill with stale bread, which they may be bringing home to hungry family members.

Or perhaps putting kids on his breadline was Luks’ way of drawing attention to the thousands of homeless children who lived on the streets or in lodging houses, working in legitimate jobs or joining criminal gangs. Access to a breadline could have kept these “street arabs,” as they were dubbed, from going to bed hungry.

[Top image: Wikipedia; second image: MCNY 93.1.1.18243; third image: National Gallery of Art; fourth image: Alamy; fifth image: George Bain Collection/LOC]