When you think of the Bronx, districts of tidy single-family attached row houses probably don’t come to mind. And that makes sense, considering the late start this northernmost borough had in terms of urban development.

The Bronx still maintained a sizable number of rural areas (and large estates owned by the wealthy) within its borders when it was annexed to New York City in stages from 1872 to 1895. The borough was too spread out, and had too few people, to build the kinds of brownstone and townhouse rows that urbanized Manhattan and Brooklyn throughout the 19th century.

But after a population boom in the early 1900s, as well as the opening of the New York City subway, row house development did come to some parts of the Bronx—including Hunts Point, when 42 two-story dwellings lining the north and south sides of Manida Street hit the market.

Instead of the brownstone or limestone homes typical of large parts of Manhattan and Brooklyn, the row houses along this stretch of the newly developed South Bronx are semi-detached dwellings in the Renaissance Revival or Flemish Revival style with bow fronts, stepped parapets, and other whimsical architectural touches.

These houses, situated on a single block between Garrison and Lafayette Avenues, make up the Manida Street Historic District. Made official in 2020, the new historic district joins others in the Bronx like the Bertine Block in Mott Haven and a section of Morris Avenue near the Grand Concourse.

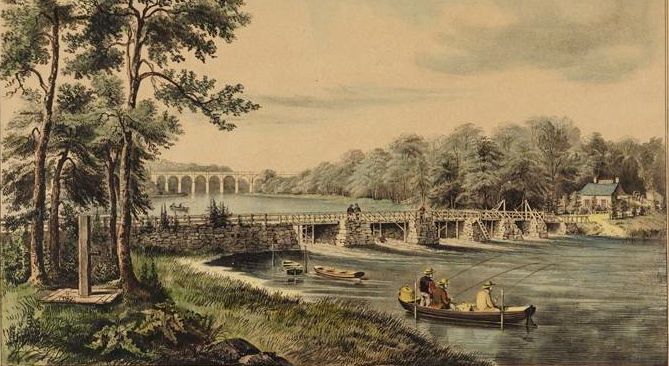

[Above, 839 and 841 Manida Street today; below, the two houses in 1939-1941]

“On both sides of Manida Street, the two-story and basement, semi-detached buildings feature mirror-image facades with rounded projecting bays, low stone stoops, simple cornices with steeply pitched parapets above, and ornamentation concentrated around the doors and windows,” stated the Landmarks Preservation Commission Report.

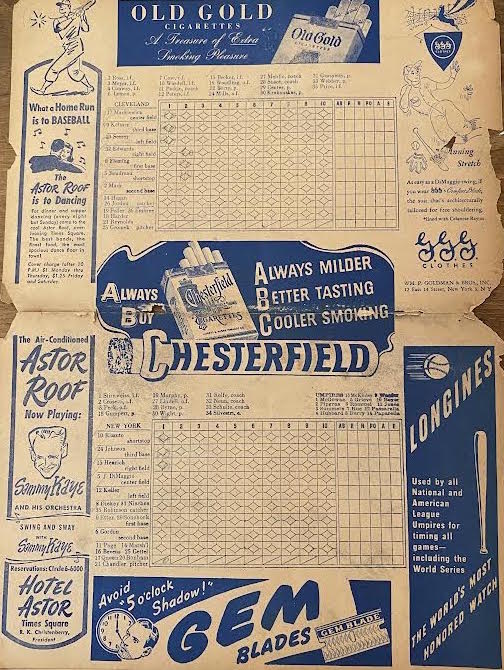

Designed by architects James F. Meehan and Daube & Kreymborg in 1908-1909, the row houses were built on speculation and advertised to potential buyers in a 1909 ad that ran in the New York Times, per the LPC report.

“These two-family houses are situated in one of the prettiest and most accessible areas of the Bronx,” the ad read. “They are in the heart of a district built up with some of the finest homes in the greater city.”

Who decided to buy one of these two-family row houses, which included the appealing option of renting one half of the house to another family and making back a little cash?

The first crop of owners were mostly immigrants, primarily Russian Jews, according to the LPC report. “In addition, there were several German households along the block, with a few Irish and Italian residents as well,” the report added.

Like much of the rest of the Bronx, Manida Street maintained its middle-class status as the 20th century continued. Residents worked as “tailors, teachers, diamond dealers, and leather merchants,” noted the report. Some worked at the nearby American Bank Note Company Printing Plant.

Demographics changed as the century continued, of course. While the Bronx’s fortunes turned, the row houses on Manida Street and the sense of a middle-class island in Hunts Point remained intact.

“In the 1970s, when the Hunts Point section of the Bronx became associated with drugs, crime, and prostitution, a group of bow-front row houses in the 800 block of Manida Street remained an oasis of tranquillity,” wrote the New York Times in 2010.

These days, the South Bronx is a place of redevelopment, and the Manida Street row houses are part of a protected historic district. Though many of the houses reflect the bad old days of the area—with bars over bay windows, metal fences, and ornamentation on the facades missing—there’s an unusual harmony and beauty to the quiet block.

Will it be the next Park Slope? Probably not—it’s just one slender street. But never say never.

[Third photo: NYC Department of Records and Information Services]