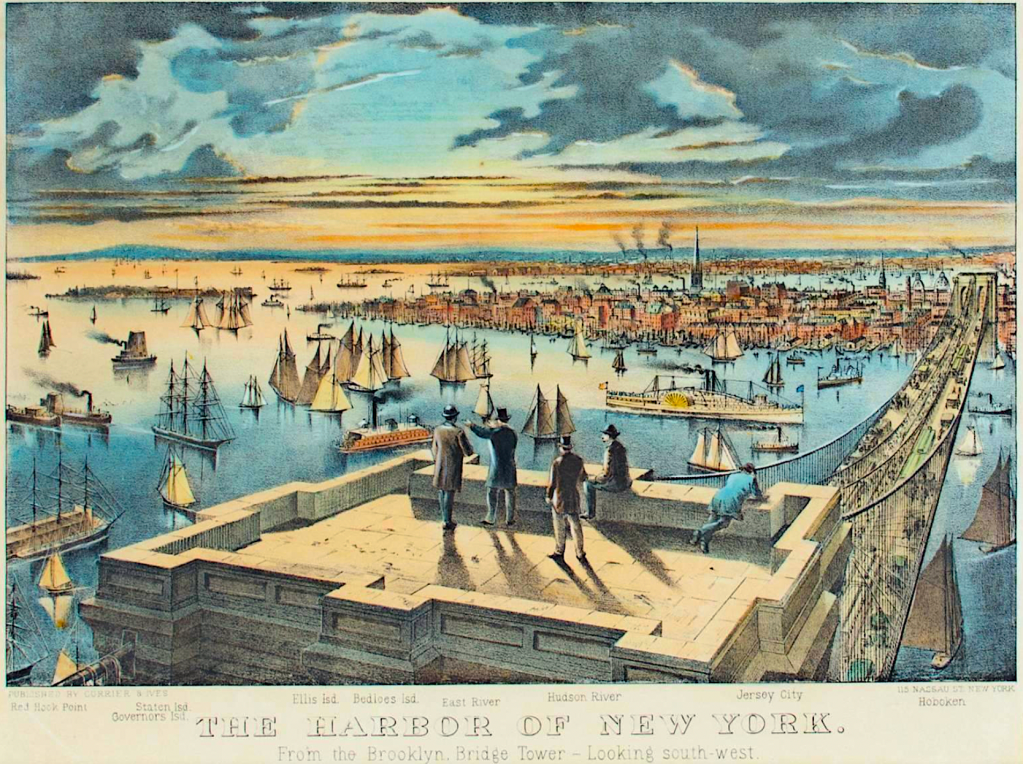

Changes came to the Brooklyn Bridge not long after this “eighth wonder of the world” linking the cities of New York and Brooklyn opened to enormous fanfare on May 24, 1883.

The toll to cross the bridge (one cent for pedestrians, a nickel for a horse and rider, and 10 cents for a horse and wagon, per history.com) ended in 1891. Eight years later, tracks were added to the bridge’s roadways so trolleys could carry people across the bridge in both directions.

But before that, in 1886, a high-profile New York welfare worker came up with a more fantastical idea: building an “ornamental palace of glass,” as Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper described it, on the top of each of the bridge’s two towers (sketch above).

These glass enclosures would serve as “grand observatories” for visitors who wanted to view the cities of Brooklyn and New York from “lofty heights,” the article continued.

How would people reach these glass enclosures? They would be whisked to the top of the towers and into the observatories by elevators, which would be enclosed in new steel framework to be added alongside each tower.

It might rank as the boldest, most unusual idea to alter the bridge ever put before city officials. But then Linda Gilbert (above), the woman who suggested it, was a bold and unusual New Yorker.

Born in Rochester in 1847, Gilbert (above in 1876) had been dubbed “the prisoner’s friend” because of her dedication to improving prisons and the lives of people residing in them. As a young woman, she used inherited family money to create penitentiary libraries, eventually building libraries at Sing Sing, the Tombs, the Ludlow Street Jail, and the New York House of Detention.

After her own funds dried up, she launched the Gilbert Library & Prisoners Aid Fund in 1876. Her need for more money to put toward her prison reform work appears to have been the reason behind her glass observatory idea.

“Gilbert proposed a modest fee for visitors, three-quarters of which would serve as direct revenue for the bridge, while the rest would fund Gilbert’s charitable and reformatory work,” wrote Richard Haw, author of Art of the Brooklyn Bridge: a Visual History.

“I am constantly hampered in my work for lack of funds,” Gilbert stated to Frank Leslie’s newspaper, bolstering her idea by adding that one of her cousins, Rufus H. Gilbert, was the inventor of the city’s first elevated railway.

She described the bridge towers as “not very ornamental.” Instead, she advocated for adding on top “two of the grandest points of elevation in the world” as long as she could be assured of getting a quarter of the receipts to put toward her prison reform work.

“The scheme will certainly attract general attention,” the Frank Leslie article concluded. In the end, of course, the glass observatories idea was DOA.

“The bridge’s trustees considered the proposal, but it went no further,” wrote Haw.

[Top image: NYPL Digital Collection; second image: Wikipedia; third image: The Life and Work of Linda Gilbert; fourth image: Currier & Ives, 1883, 1stdibs.com]