Some photographers turn their cameras to the faces of people, capturing depth and unguarded emotion in human expression and behavior.

Alvin Langdon Coburn found quiet, abstract beauty in the light and shadows of the landscape of turn of the century New York City.

[“The Coal Cart,” 1911]

Born in 1882 in Boston, Coburn received his first Kodak as a child in 1890. Infatuated with this relatively new medium, he learned the craft and experimented in the darkroom.

In his 20s, he traveled to New York City and Europe to study with greats such as Edward Steichen. Like leading photographers Steichen and Alfred Stieglitz, Coburn was part of the Pictorialist movement.

[“The Octopus,” 1912, taken from the top of the Met Life Tower in Madison Square Park]

Pictorialists “argued that photography was a creative art form, on a par with other visual arts including painting, and not simply a mechanical means of objectively recording the world,” states this post from amateurphotographer.co.uk.

“They used a wide variety of techniques to express emotion and mood, and were particularly known for producing atmospheric, soft-focus portraits and landscapes.”

[“Fifth Avenue From the St. Regis,” 1913]

Coburn exhibited photos in galleries and was commissioned to do portraits of notable men of the era, such as George Bernard Shaw and Henry James. Soon, his work took a more abstract turn.

“Like many photographers associated with Stieglitz, Coburn by 1910 sought to shed the romanticism of the pictorial movement and bring photography more in step with abstract painting and sculpture,” states the National Gallery of Art website.

“He made photographs looking down from the tops of tall buildings to explore the use of flattened perspective and geometric patterning. During World War I he became involved with the Vorticists, a group of British artists, including Wyndham Lewis and Ezra Pound, who sought to construct a dynamic visual language as abstract as music.”

[“Broadway at Night,” 1905]

“As a photographer of cities and landscapes (1903–10), he concentrated on mood, striving for broad effects and atmosphere in his photographs rather than clear delineation of tones and sharp rendition of detail,” states MOMA.

[“Flatiron Building,” 1912]

“He was influenced by the work of Japanese painters, which he referred to as the ‘style of simplification.’ He considered simple things to be the most profound,” continues the MOMA website.

Coburn didn’t stay in New York long. He moved permanently to the UK in 1912.

Coburn didn’t stay in New York long. He moved permanently to the UK in 1912.

By 1918 he had given up photography professionally, devoting the rest of his life to the study of mysticism and the occult.

He died in Wales in 1966, leaving a legacy of enchanting images of the New York of a century ago: the soft glow of early electric lights, 22-story skyscrapers casting monstrous shadows over parks and sidewalks, and the presence of powerful machinery interrupting the serene beauty of nighttime streets.

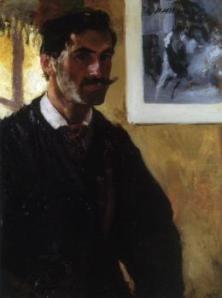

[Right: self-portrait, 1905]