You’ve likely passed New York’s most famous Alice: an 11-foot bronze of the Mad Hatter, the Dormouse, and other characters from Lewis Carroll’s classic.

You’ve likely passed New York’s most famous Alice: an 11-foot bronze of the Mad Hatter, the Dormouse, and other characters from Lewis Carroll’s classic.

This kid-friendly statue been at 74th Street on the east side of Central Park since 1959.

But there’s a lesser-known homage to Alice that predates the bronze sculpture by 23 years. It’s tucked inside Levin Playground a few minutes away.

Once a drinking fountain but since 1987 refitted with sprinklers, this granite statue features Alice, the Queen of Hearts, the Mad Hatter, the Cheshire Cat, the White Rabbit, and the Duchess.

Once a drinking fountain but since 1987 refitted with sprinklers, this granite statue features Alice, the Queen of Hearts, the Mad Hatter, the Cheshire Cat, the White Rabbit, and the Duchess.

The characters might look familiar: They were designed by the same sculptor whose animal depictions grace the Central Park Zoo.

Why two homages to Alice in one park? I’m not sure, but the fountain was dedicated to Sophie Irene Loeb, founder of the Child Welfare Board of New York City.

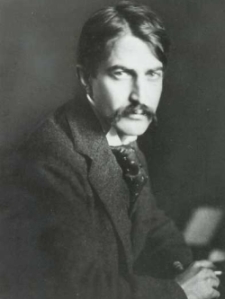

Loeb (left) spent her life helping city kids, building bath houses, implementing school lunch programs, supporting housing reform, and creating recreational opportunities in Central Park.

Loeb (left) spent her life helping city kids, building bath houses, implementing school lunch programs, supporting housing reform, and creating recreational opportunities in Central Park.

Alice also lives underground at the 50th Street subway station on the 1 train.