In 1686, Philip Jacob Rhinelander, a German-born French Huguenot escaping religious persecution in Europe, immigrated to New York.

A century later, his descendants comprised one of the richest families in Gotham. The Rhinelanders made their money as shipbuilders, sugar importers, and stewards of a vast real estate empire across Manhattan, states the Friends of the Upper East Side Historic Districts.

The Rhinelander Sugar House once on William Street, Rhinelander Row and Rhinelander Gardens in Greenwich Village, the Hardenburgh-Rhinelander Historic District on East 89th Street—all are named for 18th and 19th century family members from this old-money clan.

But there’s another landmark in Manhattan that still bears the Rhinelander name: the Rhinelander Industrial School at 350 East 88th Street.

These days, the school is a ghostly shell between First and Second Avenues, its stepped gables and terra cotta “R” on the front facade (below) behind construction scaffolding.

But within its brick walls (now sadly covered in stucco) holds the story of two Rhinelander family heiresses and the gift they gave to needy children in what was then a poor immigrant neighborhood.

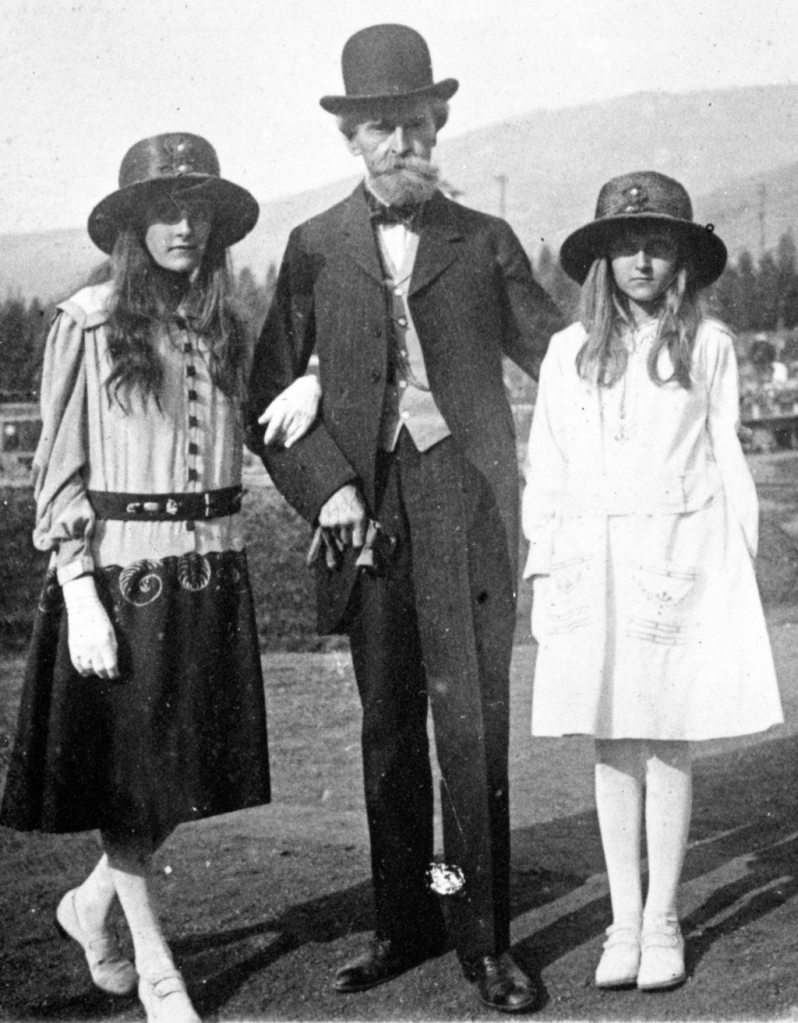

The sisters, Julia and Serena Rhinelander (in the above illustration), were born into a wealthy household at 477 Broadway in 1824 and 1829. In 1840, their father, William C. Rhinelander, moved the family to two adjoining houses that formed one mansion at Fifth Avenue and Washington Square North—at the time a fashionable enclave for Manhattan’s most elite.

In time, Julia and Serena’s sister and brother left the family mansion; their parents passed on. But the sisters, who never married, continued to live in the house at 14 Washington Square.

As heirs to a reported $50 million fortune, they didn’t have to work. Instead, they traveled, they attended social events, and they devoted themselves to philanthropy.

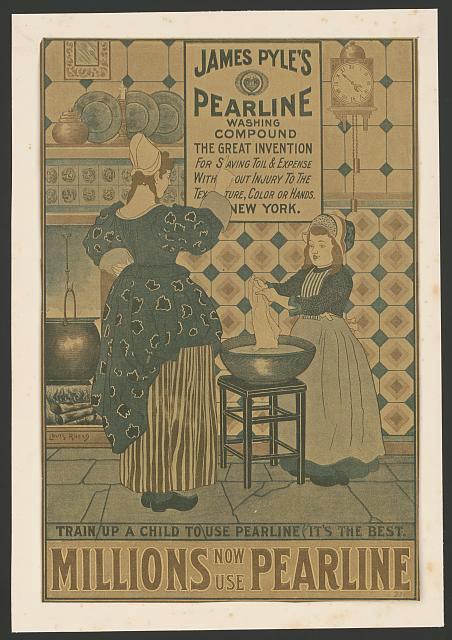

One of the philanthropic measures they decided to take on was the funding of a school that would be owned and operated by the Children’s Aid Society. The Society, launched in 1853 by Reverend Charles Loring Brace, began opening schools across New York City in the 1880s and 1890s where poor children could take regular classes while also learning a trade.

Wealthy New Yorkers donated the funds to build these schools. Julia and Serena decided they would as well, and they also donated a plot of Rhinelander family land on East 88th Street where the school would be located.

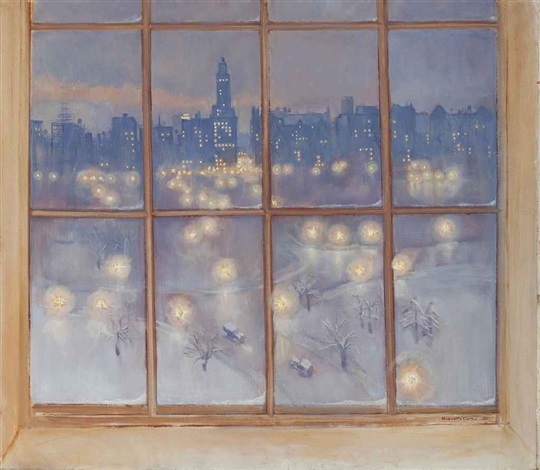

Unfortunately, Julia Rhinelander never lived to see the school completed; she died in 1890 while vacationing in France. Serena, now alone in the family mansion (below, the house on the corner), did see the Rhinelander Industrial School open in May 1891.

Designed by Calvert Vaux (the architect behind many of the Society’s schools and homes for kids), the facility was described as a “beautiful building” by the New York Times, who noted that it had space for about 300 children, including a “kindergarten, sewing, and cooking schools.”

The school thrived as Yorkville’s population boomed. “By 1902, the Rhinelander Industrial School was serving 477 children, only up through age 12 because ”the children go to work at the age of 13,” according to the annual report of that year,” wrote Christopher Gray in the New York Times in 1989.

“Boys were taught manual trades and girls were taught cooking to provide household economy to those who needed it most,” added Gray.

Serena Rhinelander died in 1914 in her mansion at 14 Washington Square, after a lifetime of donating liberally to churches and charities in her “quiet and unostentatious way” according to her obituary in the New-York Tribune.

Meanwhile, the school changed with the times throughout the 20th century. The building was remodeled in the 1950s, noted Gray, gaining its stucco facade.

It’s unclear how long classes were held and what subjects were taught. Yorkville by the late 20th century was no longer an immigrant neighborhood, and industrial schools that taught sewing and cooking had outlived their usefulness.

In 1989, the school was renamed the Rhinelander Children’s Center. As of 2014, the Children’s Aid Society was trying to sell the building to raise money for a new facility in the Bronx. Considering that the former industrial school is behind scaffolding, it appears to have been sold.

What does the next chapter hold for this relic of Gilded Age benevolence? Perhaps the school is undergoing redevelopment—or waiting for the wrecking ball.

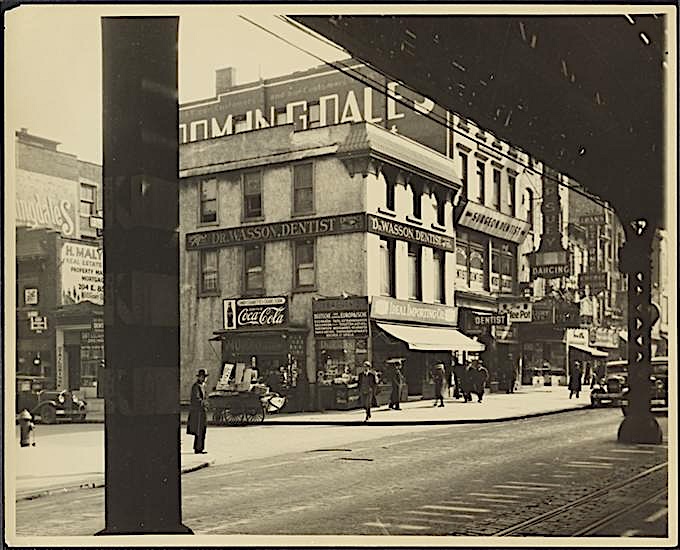

[Fourth image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services; fifth image: NYPL Digital Collections;